In the quiet hours of a sleepless night, life can be stripped bare of its illusions.

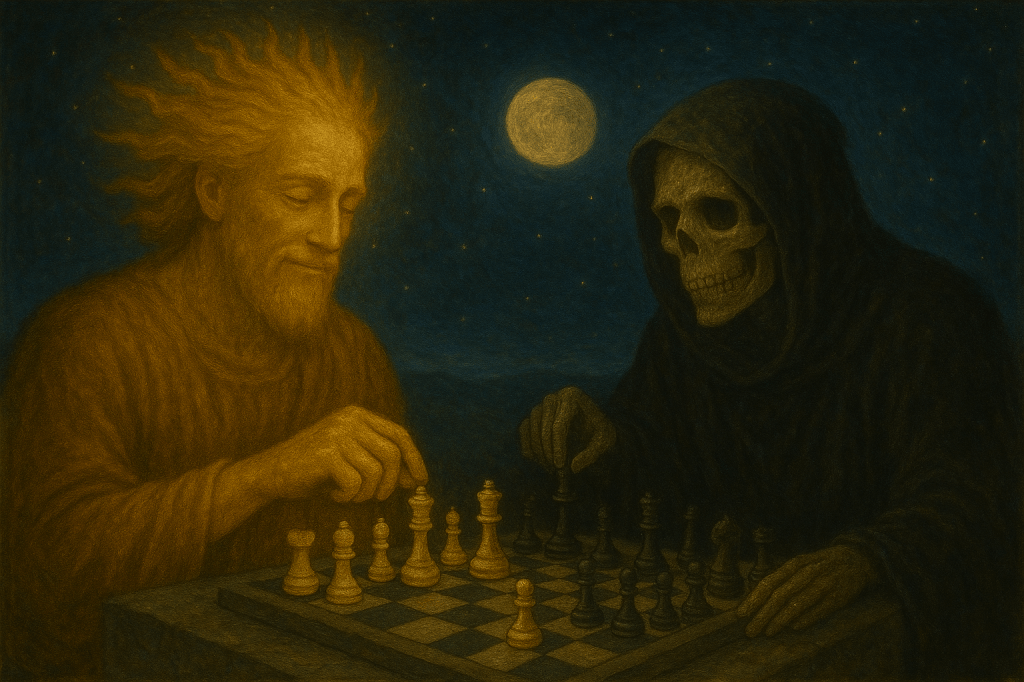

Sometimes I feel like we are just chess pieces – shaped differently, valued differently, moving with varying freedoms, and yet, all bound by the same board and the same end: to return to the box.

We imagine ourselves as masters of the game, but in truth, we are moved by unseen hands: chance encounters, historical tides, biologies, social conditions, and whims of fortune. Even our so-called “strategies” often emerge as a response to moves already made upon us.

We think our days as a journey we direct, but in actuality we are all born on the board. The game began long before our arrival, and it will continue long after we are gone. The squares are laid, the rules are fixed, the pace is set by forces beyond our reckoning.

The ancients knew this truth.

The Chinese have long spoken of the interplay between Yin (陰) and Yang (陽), the unending rhythm of day yielding to night, night yielding to day. They are not just opposites, they are the players of the game itself. And we, are the pieces moving within their eternal alternation. A Stoic might nod here, recognizing in this a mirror of their own belief: the cosmos moves according to its nature, indifferent to our desires.

Epictetus tells us that peace comes from knowing what is within our control and what is not. The Daoist would say: not only must we accept the flow, we must learn to move with it, to act without forcing – this is Wu Wei (無為), “effortless action.”

Marcus Aurelius wrote that life is but a play, and we must act our part well before stepping off stage. Some of us are born as pawns, steady and unassuming; others as knights or queens, capable of strange leaps and sweeping moves. Yet the end is the same for us all. This is neither reason for despair nor for fatalism, it is an invitation to focus on how we move, not whether we will win. We do not control the shape of the board, nor the rules of the game, but we can decide with what spirit we advance or retreat. A pawn who moves with dignity may hold more victory than a king trembling at the end.

We often have the tendency to overestimate our agency and underestimate the quiet, systemic forces around us. We often forget that this world, much like the chess board, is full of constraints and possibilities. We may bristle at the limits shaped by different circumstances, but to resist the truth of them is to exhaust ourselves against the edges of the board. Acceptance – what the Stoics called amor fati, the love of one’s fate – is not passive surrender. It is the art of aligning our will with reality, so that each move, however small, carries weight and purpose.

To me personally, knowing our own limit also offers a paradoxical freedom: when the myth of total control dissolves, the pressure to “win at all costs” softens. We are freed to act well in each moment, not for the illusion of permanence, but for the honor of playing our part with intention.

The Daoist sage does not curse the board for being square. They study the currents of the game, the direction of the other pieces, the pauses between moves. The Stoic, too, understands this: the universe is change, and our role is to live in harmony with it. In chess, as in life, even the most brilliant strategy cannot prevent the final return to the box. The Stoic accepts this without bitterness, the Daoist accepts it without fear.

And so, perhaps the wisest move is not to cling to the board, nor to fear the box. Between the opening move of dawn and the checkmate of night, we have the space to create meaning – we do not need to conquer the board to live well upon it. Our meaning is not in the victory, but in the quality of each move, whether bold or humble, forceful or still. When night comes and the hand gathers us back into the box, let us have played in such a way that our moves, however small, were in harmony with ourselves.

In the end, the Daoist says: flow with the board. The Stoic says: stand firm upon your square.

Between dawn and dusk, we can play with courage, with grace, and with the quiet knowledge that our part is inseparable from the whole.

When the box closes, let it be said: this one moved well.